When “Be More Collaborative” Really Means “Carry the Damage”

When someone tells you to “be more collaborative”, check who is about to avoid a decision.

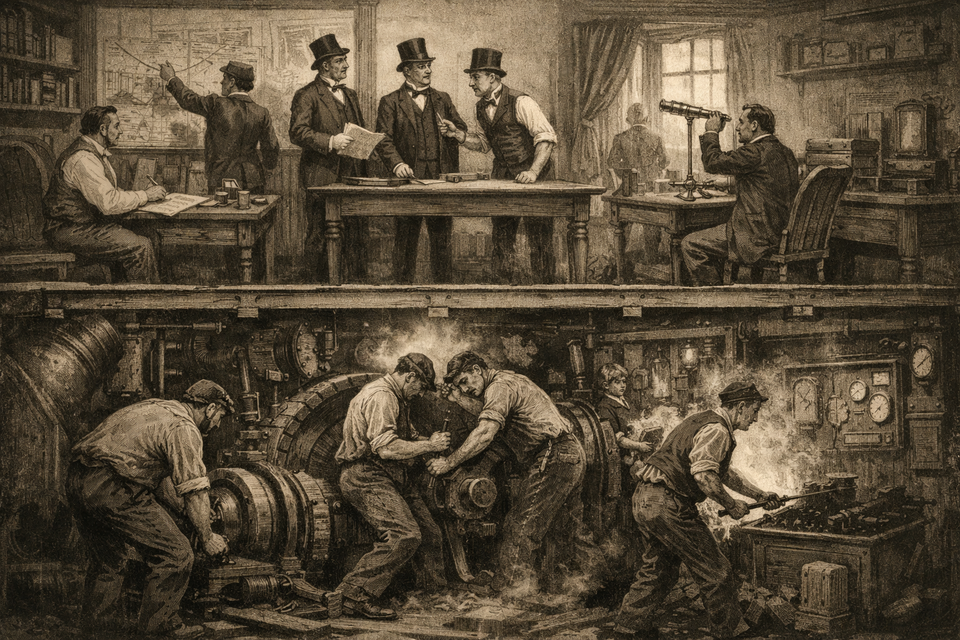

In theory, and when properly implemented, collaboration sounds virtuous. Teamwork. Alignment. Shared ownership. In practice, in many organisations, it has become something else entirely: a mechanism to redistribute pressure downward without redistributing authority.

This is not a critique of teamwork. Real collaboration matters. What passes for collaboration today, however, often functions as a one‑way valve: organisational stress flows toward those who still carry accountability.

Collaboration as a Signal

Calls for “more collaboration” rarely appear when things are clear. They tend to surface when it is already too late, when priorities conflict, ownership feels risky, or trade‑offs should have been made but were not.

Instead of deciding, leaders and product roles widen the room. Meetings multiply. Stakeholders are invited. Opinions circulate. Commitments do not.

The language sounds inclusive, but it often relies on an altered vocabulary, a post‑modern habit that pretends to describe reality while actually obscuring it. This linguistic drift reinforces organisational fragility, replacing shared understanding with conditioned responses. Behaviour is shaped through repetition rather than truth.

At this point, a critical distinction disappears: early collaboration versus late collaboration. Early collaboration happens at design time, when intent, constraints, and trade‑offs can still be shaped. Late collaboration appears as damage control, once decisions have been deferred and risk has already materialised. One creates clarity. The other merely redistributes pain.

Where the Damage Lands

In these environments, collaboration is not evenly distributed.

Engineers absorb the cost:

- Context switching across half‑formed ideas

- Rework driven by delayed clarity

- Emotional labour to preserve fragile alignment

- Technical risk without decision authority

Others retain optionality. Engineers retain responsibility.

This asymmetry compounds over time. A typical example in many modern IT organisations, is a set of incompetent customer‑facing teams demanding “more collaboration” from platform teams. What is sought is not shared thinking, but compliant execution, labour to fulfil orders, not engineers to build leverage.

Order‑taking platforms execute requests as they arrive. They optimise for responsiveness, appeasement, and short‑term relief. Leverage‑building platforms design constraints, abstractions, and interfaces that reduce future demand. One absorbs work. The other amortises it.

When collaboration forces platforms into order‑taking mode, leverage never materialises. Costs compound instead of flattening. Every request feels urgent. Every delivery feels bespoke. The platform becomes permanently expensive to operate.

Interfaces fail to stabilise. Roadmaps drift. Decisions remain reversible. Trust erodes as effort increases without a corresponding increase in authority.

The Moral Hazard

In this trap, the most "collaborative" teams often carry the greatest organisational debt.

They say yes. They adapt. They compensate for upstream vagueness. They make systems function.

By doing so, they shield the organisation from the consequences of poor leadership or abusive peer teams, precisely because this absorption is comfortable for those in power. A moral hazard forms: the more a team absorbs, the less incentive there is to address the root cause.

This is why strong contributors leave first. They recognise exploitation early. They understand when resilience substitutes for clarity.

What Real Collaboration Requires

Healthy collaboration has a cost, and that cost must be explicit.

It requires:

- Clear ownership before discussion

- Explicit trade‑offs, written down

- Decision‑makers present and accountable

- Acceptance of risk, including the possibility of failure

- Psychological safety for truth, not comfort

- Interfaces that stabilise over time

Ownership without the freedom to fail is not ownership. It is liability without authority.

Without these conditions, collaboration becomes noise presented as virtue.

A Leadership Mirror

Ask yourself this: When collaboration increases, who actually takes the risk?

If the answer is “the executing teams” rather than “the decision‑makers”, collaboration has replaced accountability.

Where no one accepts the possibility of failure, decisions decay, language softens, and collaboration becomes a shield against responsibility.

That is not alignment.

It is comfort masquerading as leadership.

Member discussion