The Sponsorship Gap

Some organisational failures repeat so often that they stop being accidents. The sponsorship gap is one of them.

Introduction

Organisations often claim to value senior expertise, systems thinking, and leadership maturity. Yet, time and again, they place experienced leaders or experts into complex roles without providing the conditions required for that expertise to matter. When outcomes fall short, the conclusion is rarely that the system failed. Instead, the individual is quietly reclassified as “not senior enough”, “too conceptual”, or “lacking executive presence”.

This pattern has a name: the sponsorship gap.

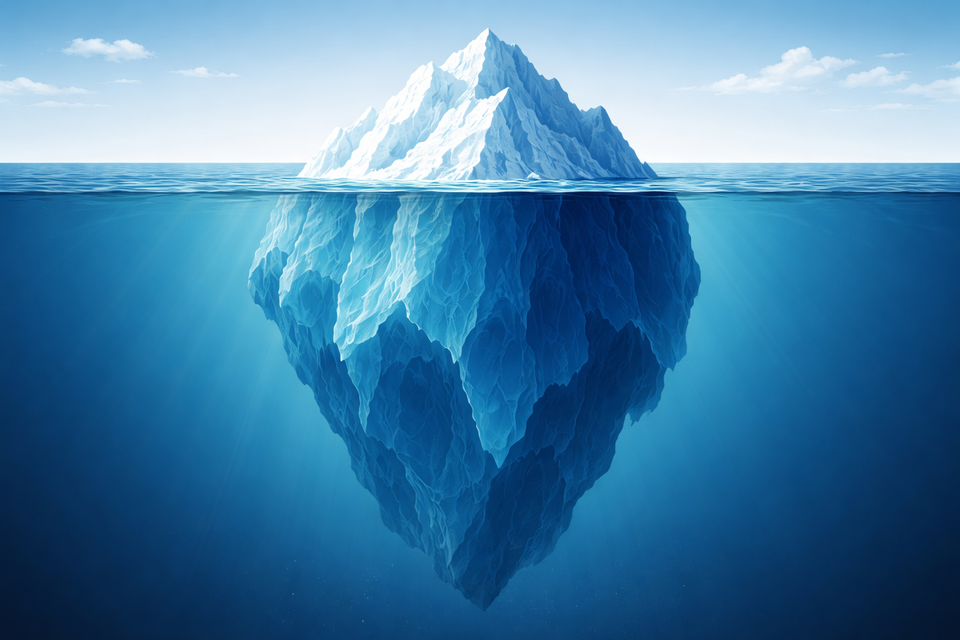

A sponsorship gap exists when responsibility and expectations are granted, but authority, protection, and adoption mechanisms are withheld. The expert is present. The mandate is not.

Expertise Is Not Sponsorship

Expertise answers the question: what should be done?

Sponsorship answers a different one: will the system allow it to happen?

Most organisations conflate the two. They assume that hiring a senior expert automatically solves structural problems. In reality, expertise without sponsorship is inert. It produces ideas, diagnoses, and plans, but no durable change.

Sponsorship is not encouragement or verbal support. It is the active, and often uncomfortable, work of:

- enforcing adoption,

- arbitrating priorities,

- resolving ownership conflicts,

- and absorbing political friction on behalf of the person doing the work.

Without this, expertise is reduced to advisory noise.

Responsibility Without Sponsorship Is a Trap

The sponsorship gap becomes most visible when responsibility is assigned without the means to exercise it.

Common signals include:

- accountability for outcomes, but optional adoption of solutions;

- constantly shifting priorities driven by external pressure;

- fragmented ownership across teams or domains;

- escalation paths that are discouraged or undefined.

In such environments, failure is not accidental. It is designed in.

The individual absorbs the complexity, the ambiguity, and the pressure, while the system retains plausible deniability. When results are mixed, the gap is retrospectively reframed as a personal limitation rather than a structural one.

The Retrospective Rewrite

Once the organisation moves on, a familiar narrative often emerges:

- “They were very strong technically, but…”

- “They were more of an expert than a leader.”

- “We needed someone more senior for this phase.”

This rewrite serves a purpose. It absolves the organisation from examining whether it ever intended to sponsor the work in the first place.

The uncomfortable truth is that many organisations want the benefits of senior expertise without paying the cost of sponsorship. That cost includes conflict, explicit trade-offs, and visible executive ownership.

Why the Sponsorship Gap Persists

Sponsorship is expensive. It requires leaders to:

- say no on behalf of others,

- enforce decisions that upset local optimisations,

- and remain accountable when outcomes take time to materialise.

In contrast, unsponsored expertise is cheap. Ideas can be harvested. Structures can be reused. Outcomes can be claimed selectively. When tension arises, the individual can be repositioned or replaced.

This dynamic is especially common in platform, transformation, and systems roles, where impact depends less on individual brilliance and more on organisational alignment.

A Repeating Pattern, Not an Isolated Case

Perhaps the most damaging aspect of the sponsorship gap is that it rarely occurs once. In many organisations, a familiar cycle unfolds:

- an expert is brought in to diagnose and structure a complex problem;

- constraints, misaligned incentives, or fragmented authority limit real execution;

- before the work can fully mature, another expert is hired or repositioned to “accelerate” or “course-correct”;

- the original conditions remain unchanged.

The individuals change. The pattern does not.

Over time, this cycle can repeat across multiple departments, functions, or transformation efforts. Each iteration reinforces the belief that the issue lies with the people involved rather than with the organisation’s inability or unwillingness to sponsor systemic change.

The cost is cumulative: institutional memory erodes, trust declines, and the organisation becomes adept at replacing experts while preserving the very conditions that caused the previous failures.

The Human Cost of the Sponsorship Gap

While the sponsorship gap is damaging for organisations, it is often far more destructive for the individuals caught inside it.

Experts rarely enter these roles cynically. They are drawn in by what appears to be genuine intent: clear language about transformation, explicit recognition of systemic problems, and a narrative that positions them as catalysts for meaningful change. The invitation feels serious. The trust appears real.

In organisations where the sponsorship gap has become part of the organisational DNA, this is not accidental. The rhetoric is polished. The ambition sounds credible. The honeypot tastes genuine.

People believe the saviour story because, at the level of words and intent, it often is sincere. The failure comes later, when action does not follow language. Adoption remains optional. Trade-offs are deferred. Authority stays fragmented. Sponsorship never materialises.

By the time the gap becomes undeniable, the individual has already paid the price: reputational risk, emotional fatigue, and the quiet internalisation of a failure that was never fully theirs to carry.

Fragmentation After Extraction

In some cases, the organisation does not reject the expert’s work outright. Instead, it selectively extracts fragments from it: ideas, emergent grown leaders, partial outcomes.

These fragments are then redistributed across the organisation, often rapidly and opportunistically, detached from the original system in which they made sense. What follows can resemble scavenging rather than stewardship: pieces are claimed, rebranded, and redeployed, but rarely owned end to end.

Crucially, the organisation that failed to consistently onboard or sponsor the expert also fails to consistently use what it takes. Without shared context, authority, or sustained sponsorship, the extracted ideas and outcomes are applied unevenly, decay over time, or are quietly abandoned.

The result is a paradox: the organisation appears to move forward by absorbing visible artefacts of progress, while systematically preventing those artefacts from compounding into durable change.

Closing

The sponsorship gap is not a failure of individuals. It is a failure of leadership systems.

Until organisations learn to distinguish expertise from sponsorship, and to provide both intentionally, they will continue to repeat the same pattern: hire senior people, constrain them structurally, and later question their seniority.

The result is not just wasted talent. It is institutional amnesia, disguised as progress.

A Final Clarification

This is not an argument against hiring experts, architects, or senior leaders.

On the contrary, organisations increasingly need people who can reason systemically, operate across boundaries, and design for scale rather than local optimisation. The point of this article is simpler and more demanding: expertise only delivers value when it is explicitly sponsored.

Sponsorship means more than endorsement. It requires clear mandates, enforced adoption, protected decision space, and visible executive ownership over time. Without these conditions, even the strongest expertise will fragment, decay, or be misattributed.

Closing the sponsorship gap is not about finding better people. It is about building leadership systems that allow expertise to compound rather than be consumed.

Member discussion