The Electric Board and the Cost of Cutting Corners: A Story of Engineering, Responsibility, and Recovery

What a failing electric board revealed about technical debt, leadership, and the peril of tolerating fragility.

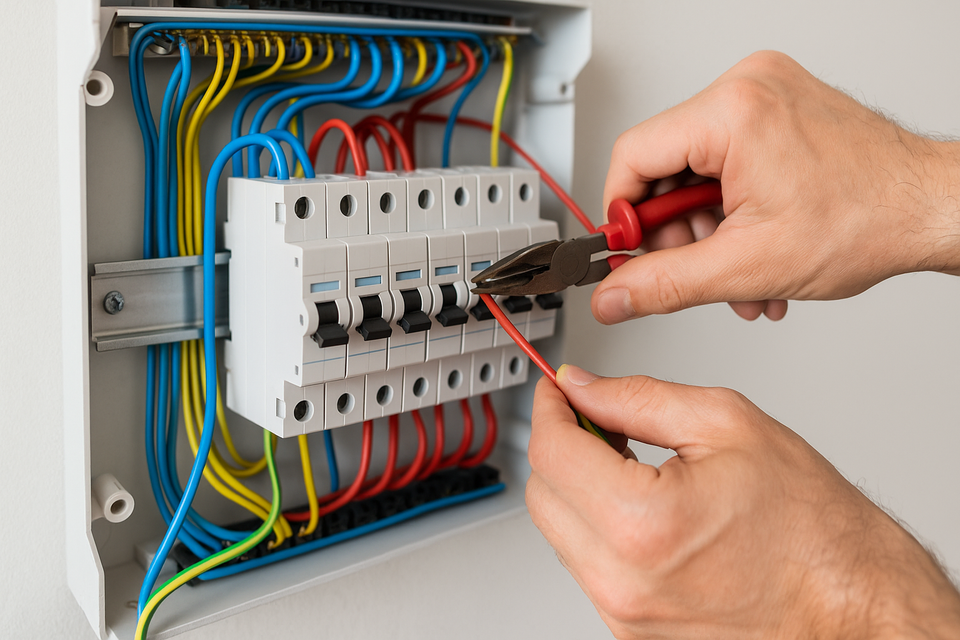

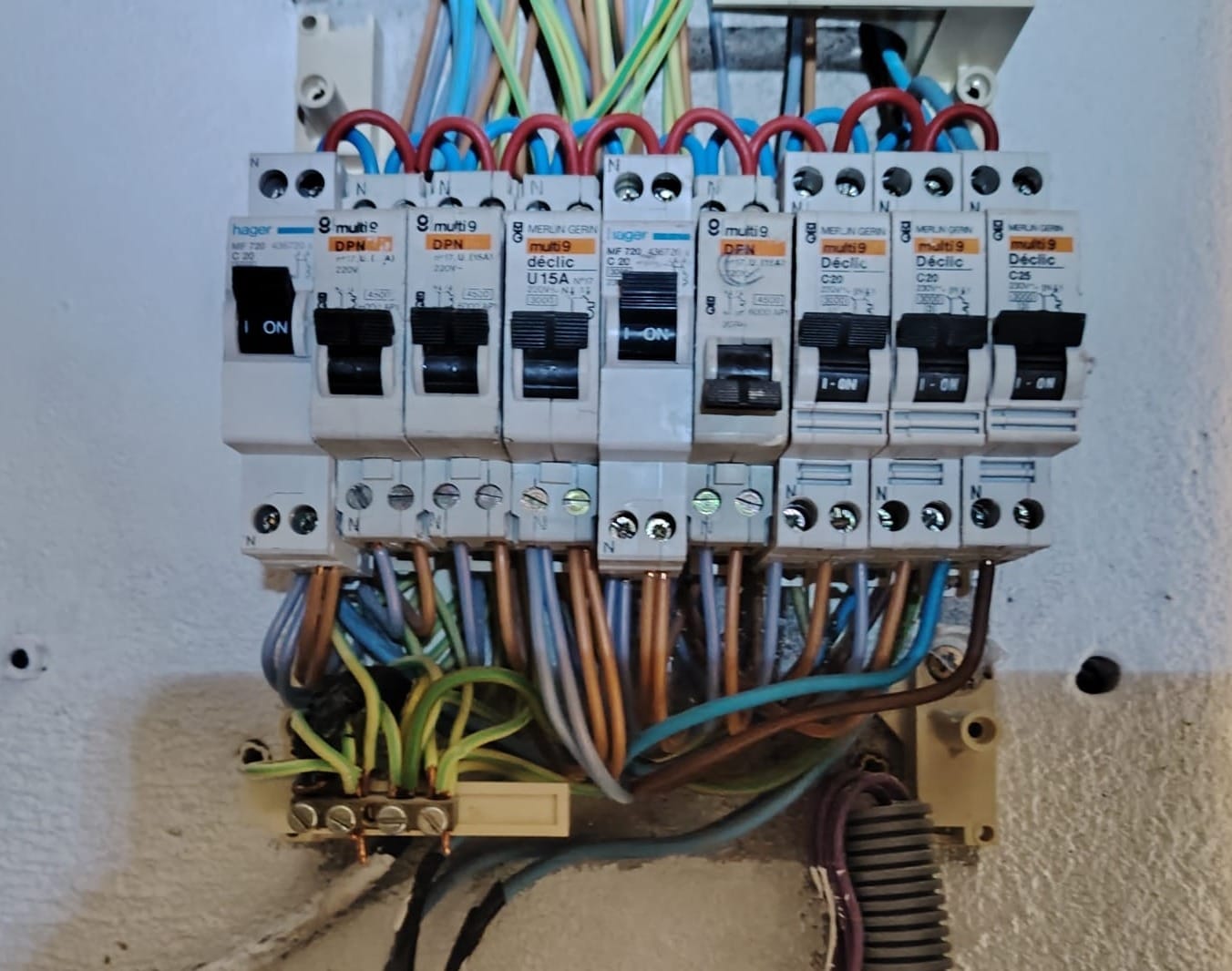

When I opened the electric board, I did not expect to find chaos. After all, it had been installed by the previous owner, someone who prided himself on being an expert in construction and building systems. His reputation preceded him. And yet, what lay behind the metal panel was not just a mess . It was a quiet act of negligence. Disconnected ground wires. Poorly routed cables. Missing circuit labels. At best, it was a puzzle. At worst, it was a fire waiting to happen.

That board told a story. Not just about electricity, but about how systems fail, not with a bang, but with the slow accumulation of corner-cutting, indifference, and misplaced trust.

This article is not just about an electric board. It is about the cost of taking shortcuts, the invisible risks that build up over time, and the effort it takes to restore order. It is also a reflection on craftsmanship, responsibility, and what it means to build something that lasts.

Visible and Invisible Costs

The visible signs were easy enough to spot. Wires that overlapped in confusing patterns. Unlabelled fuses. A complete lack of modularity. These were the kinds of errors even a layperson could notice. But the deeper problems, the invisible ones, were more insidious. Grounding failures. Oversized breakers. Potential non-compliance with safety norms. The kind of risks that only manifest after something goes wrong.

And that is precisely the danger. When a system does not fail immediately, its flaws are mistaken for acceptability. Like a team that continues to deliver despite dysfunction, or software that "works" despite growing technical debt, the electric board operated in silence, but unsafely.

In systems thinking, this is known as a “shifting the burden” dynamic. We postpone the real solution because the system continues to function. But the burden does not disappear: it shifts forward in time. It accrues interest. And when it comes due, the cost is far greater than the original fix would have been.

Professionalism Without Craftsmanship

What disturbed me most was not just the poor layout or safety violations. It was that this board had been built by a certified electrician. A professional. Someone with the right papers and likely years of experience. But clearly, not someone who cared about standards. Or clarity. Or craft.

There is a lesson here.

Credentials do not guarantee quality. Authority does not guarantee responsibility.

We see this everywhere: in software, in management, in politics. People hide behind titles while delivering substandard results. They may comply with the letter of the rule, but not the spirit.

Craftsmanship is different. It implies pride. Discipline. An internal standard that does not require supervision. No detail is left aside. Every wire, connection, and label matters. Work complies to standards not out of obligation, but out of conviction. It is what separates someone who wires a board to pass inspection from someone who wires it to protect a home.

In technology, we suffer the same phenomenon. We hire engineers, but we rarely ask: do they build like craftsmen? Do they document for the next person? Do they think in systems, or just in components?

Too often, we celebrate delivery over durability. But what we build reflects what we value.

Iterative Repair in a Broken System

Of course, once the flaws were discovered, the question became: what now?

The full rewrite, a complete board replacement, would have been ideal. But ideal is expensive. Ideal requires time, disruption, permits. And so, like many leaders inheriting legacy systems, I faced a more realistic challenge: how do I make this safer, in increments, under constraint?

The first step was to establish a baseline: no more unsafe wiring. No open grounds. No unidentified breakers. Each step forward, each investment of time or money, had to bring measurable value:

- The first step was to address the most critical fire risks. The water heating system had been persistently overloading its circuit, creating a severe hazard. We began by downsizing critical breakers, reducing the risk of fire by an estimated 70%, a significant mitigation.

- A second iteration brought that figure up to 85%. After weighing cost and residual risk, we prioritised a secondary circuit to protect the water heating system and planned for an RCBO installation, a clear move from mitigation to remediation.

- We are now approaching full compliance with applicable standards.

Each decision, each improvement, was deliberate and measurable. In hindsight, it is alarming how many times this board could have ignited a fire before any of these corrections were made.

Next, we prioritised clarity: labelling circuits, mapping connections. Over time, we aimed to get closer to standards. We put in safety nets, literally and figuratively, to contain risk while buying time.

This is what recovery looks like in the real world. Rarely do we get the luxury of starting over. Most often, we inherit the cost of other people’s shortcuts, and we must fix it piece by piece. It is frustrating, yes. But it is also the work of responsibility.

In platform engineering, in team culture, in leadership, the same logic applies. The fix is rarely glamorous. But without it, the system degrades further. The difference is: in software, failure may delay a user. In electricity, it may destroy a home.

Standards Are Not Bureaucracy — They Are Trust

One of the greatest lies we tell ourselves is that standards are just paperwork. In fact, they are the opposite: they are pre-agreed contracts of safety, clarity, and quality. When we follow a standard, we are not being rigid. We are creating trust between the builder and the user, the system and the maintainer, the present and the future.

That electric board was not just a technical mess. It was a betrayal of trust. Someone had to do things right, and instead delivered something that only looked finished. That is what makes systemic risk so dangerous: it often hides behind a veneer of completeness.

Rebuilding to standard was more than a compliance exercise. It was an act of repair, not just of the board, but of trust in the system.

And that trust begins with doing things the right way. Every time.

- Do not cut corners.

- Follow acknowledged patterns.

- Measure outcomes at every step.

- Leave the place cleaner than you found it.

- And never consider the work complete until every acceptance criterion is met, with no room left for improvisation.

This discipline does not slow you down. It sets you free because a reliable system built on principled foundations does not need to be revisited tomorrow.

Fear Is the Enemy of Repair

One of the most dangerous instincts when faced with a fragile system is to leave it untouched. The fear of making things worse can be paralysing, especially when the system still appears to function. But that fear is deceptive. It preserves dysfunction. It protects fragility. And it stops improvement before it can even begin.

When we first confronted the electric board’s condition, there was real hesitation. What if intervening triggered a failure? What if the cost ballooned? What if we uncovered more than we could handle? But we acted anyway, not recklessly, but with courage and method. We confronted the system’s weaknesses directly, knowing that progress would mean disrupting the illusion of stability.

You do not improve by protecting your comfort zone. You improve by confronting what is broken, no matter how delicately it was balanced. Progress demands boldness. Compliance demands clarity. And safety demands that we stop tolerating fragile systems just because they have not failed, yet.

There is no room for fear. And no place for comfort zones. Not in engineering. Not in leadership. We must also break the myths that keep systems stagnant. Nothing is too complex. Nothing should intimidate. And if it does, the answer is not retreat, but clarity. Apply agile principles: inspect, adapt, reduce. Break it down further. Simplify it until you understand it fully. Modify it until you own it. That is how fragile systems become strong, and how fear turns into confidence.

Final Reflections: What We Build, We Become

In the end, the electric board became more than a home improvement project. It became a metaphor for much of what goes wrong in engineering, leadership, and modern work.

When we cut corners, the cost is not always immediate, but it is always real. When we mistake credentials for competence, we put others at risk. And when we treat standards as bureaucracy rather than scaffolding, we invite failure into the very structure we are meant to secure.

But there is another lesson. When we recognise failure, we are not helpless. We can fix. We can iterate. We can raise the standard, if not all at once, then one circuit at a time.

The difference between disaster and resilience often comes down to a single decision: to act.

To say, "this is not acceptable," and begin the long but necessary process of putting things right.

This defines leadership. This defines engineering. And sometimes, that begins with opening the panel, and daring to look.

The board is now safer. More importantly, the mindset surrounding it reflects greater clarity and responsibility.

"The bitterness of poor quality remains long after the sweetness of low price is forgotten." — Benjamin Franklin (attributed)

Member discussion