Speed Is Not a Culture Problem. It Is a Systems Problem.

As a fractional CTO, I see a recurring executive reflex: when performance falters, we reach for culture. What we need is structure.

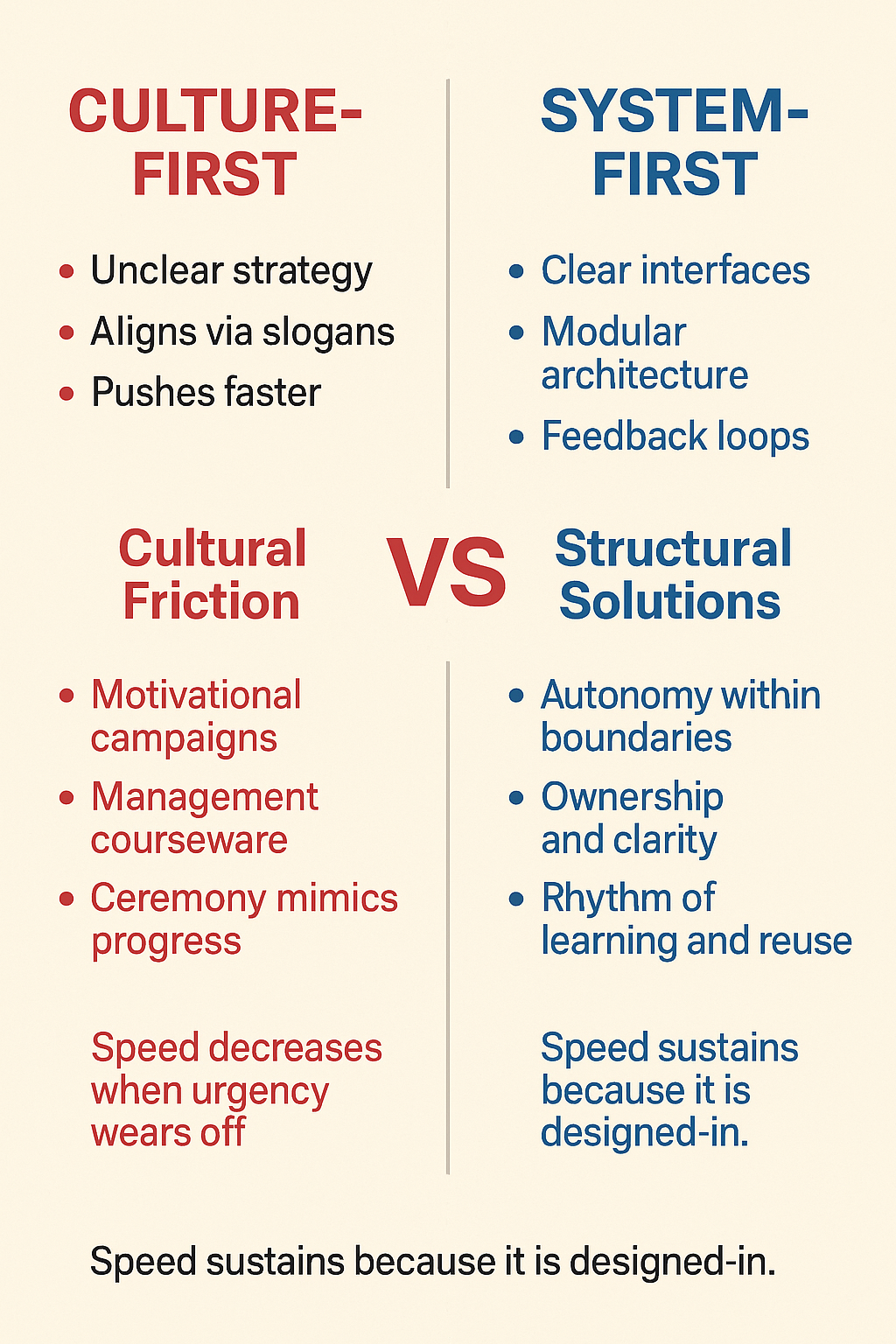

When teams move slowly, we in executive roles often reach for culture. They assume the issue lies in mindset, motivation, or accountability. But speed, true, sustained, system-level speed, is not a cultural trait. It is an emergent property of structure, interfaces, and clarity. Fixing it requires systems thinking, not slogans.

Culture influences how people behave. But systems determine what behaviour is possible. Organisations that scale speed without chaos do not coach their way there, they design for it.

Misdiagnosing the Problem: The Windowpane Fallacy

Executive overreach rarely resolves systemic drag. It reveals a lack of system trust.

As executives, we often attempt change with our noses against the glass. We try to observe everything, intervene directly, and mandate improvements. The result is a sequence of surface-level corrections: more meetings, more metrics, more visibility. But looking harder does not provide deeper insight. It reveals activity, not dynamics. Without the right metric or frame, one can mistake busyness for progress and visibility for understanding. This confusion makes exercises like OKRs so difficult to execute meaningfully. To correct this misdiagnosis, we must revisit the roots of system literacy in modern management. What is missing is not effort, but structural clarity, a view of the system that connects intention to outcome.

Teams do not slow down because they lack motivation. They slow down because they are entangled in unclear dependencies, incoherent incentives, and systems that punish flow. These frictions are structural, not personal. Addressing them requires deliberate attention to the design of the work environment and its dynamics. This is where the art of system thinking must become present at every stage, across every function.

It is not a concern for engineering alone. One can easily imagine the power of a company where system thinking prevails across marketing, sales, and operations as well. For instance, the persistent challenge of building and sustaining a healthy sales funnel is rarely a matter of individual effort or cultural motivation. It is a structural problem, involving interface clarity between marketing and sales, feedback latency from leads to insights, and unclear ownership of handoffs. A properly applied system thinking approach could reframe the entire process, treating it as an interconnected loop rather than a static pipeline.

A system-literate finance function, for example, considers budget cycles not as constraints but as rhythm design. Budgets define what kinds of change are possible over time, and when. In HR, system thinking reframes performance management as feedback loop design. It shifts focus from evaluation to enablement. Even in product development, systemic awareness changes how discovery and delivery integrate, ensuring insight flows continuously into build work, rather than being front-loaded and forgotten.

Retrospectives, stand-ups, and coaching may help reveal discomfort, but they cannot resolve systemic drag. They only describe its symptoms.

The Origins We Forgot: Rediscovering Systems Thinking

Agility once meant structure, feedback, and motion, not mindset coaching.

Toyota never scaled excellence through slogans. It built a system, a socio-technical , —where quality, speed, and learning were entangled. Early Scrum was not a delivery ritual; it was a metaphor for living systems. Inspection, adaptation, and transparency were meant to create feedback-rich environments.

But modern management culture often strips agility of its systems roots. What remains is a culture of practices, not a system of motion. We call for mindset shifts instead of examining interfaces. We pursue servant leadership without questioning structural ownership. The result is cultural theatre.

And increasingly, system theatre. That looks like RACI charts with no reinforcement, maturity models filed away in strategy decks, or dashboards that expose problems but never trigger decisions. These practices provide the illusion of awareness without commitment.

Visibility without consequence is not transparency. It is overhead.

To move faster, we must remember the origin: structure first, then behaviour. Systems produce patterns.

Structural Answers to Speed

Real acceleration comes from architecture, not urgency.

Systems that scale well do not rely on centralised control. Instead, they define boundaries, interfaces, and invariants, then allow autonomy within them. This distinction between governance and guidance becomes essential. Governance provides clarity and accountability. Guidance provides room for creativity and resilience.

The best systems empower teams by enabling choices that are local, timely, and aligned with global purpose.

This is not about passive autonomy. It is about freedom bounded by purpose and interface clarity.

Speed is not about how fast people try. It is about how little friction exists between intent and execution. In a healthy system, the following are true:

- Teams know what they own

- Interfaces are designed, not assumed

- Timeframes are aligned to reuse and feedback. When timeframes are driven solely by roadmap optics or quarterly outputs, the system fractures. Reuse fades, technical debt rises, and learning loops collapse.

- Constraints are explicit

Speed that ignores systemic timing is not acceleration. It is erosion.

This is the foundation of the Fluid Organisation model. Tools like Org Re (Organisation Resonance), Entropic Pressure, and TQS (Transduction Quality Score) allow leaders to measure not effort, but motion.

- Org Re evaluates how well roles, responsibilities, and interfaces resonate with the organisation's operating rhythm.

- Entropic Pressure tracks the accumulation of systemic drag and complexity as structural alignment decays.

- TQS quantifies the quality and adaptability of a system's outputs across time, based on feedback and reuse loops.

We can begin to see whether the system is producing healthy acceleration or fragmenting under ad hoc coordination. Where traditional management might interpret slowness as disengagement, a systemic approach looks at signal decay, interface congestion, and unclear constraints.

When interface maturity is low, change becomes slow and brittle. When ownership is unclear, feedback loops break. When governance is manual, agility stalls. These are not cultural failings. They are architectural ones. And these structural truths redefine not just delivery, but how leadership itself is identified and cultivated.

Leadership Reframed Through Systems Thinking

Those who shape flow, not just effort, become the future of leadership.

The shift towards system thinking does not affect delivery outcomes alone. It redefines how leadership is recognised and how individuals advance within the organisation. In many companies, progression is often based on visibility, responsiveness, or the ability to handle increasing complexity through direct effort. These traits, while occasionally useful, do not scale.

When organisations adopt a systems-first lens, the criteria for leadership maturity evolve. Those who can identify friction patterns, design better interfaces, and align feedback loops become critical enablers of flow. These individuals demonstrate structural thinking. They build frameworks that multiply the efforts of others rather than merely absorbing more tasks themselves.

Career development, in this context, shifts away from performative alignment and towards architectural influence. The leaders who reduce reuse drag, clarify ownership boundaries, or decouple bottlenecks are not only contributing to delivery efficiency. They are transforming how the system behaves over time. Their work removes invisible barriers, accelerates collective learning, and stabilises long-term adaptability.

Therefore, in system-literate organisations, advancement is less about personal output and more about ecosystem leverage. Those who understand structure, shape flow, and build with intention will find themselves increasingly relied upon. Not because they are louder or more reactive, but because they expand the organisation's capacity to act with precision and coherence.

This is what leadership should reward. And this is what we, as executive stewards, must begin to recognise and scale.

Change does not happen at the glass. It happens when leaders step back far enough to see structure. This is not abdication but conscious design. As executives, we must:

- Stop treating culture as the primary lever

- Start investing in system visibility

- Empower teams by designing clear interfaces

- Move from exception handling to systemic pattern recognition

You do not accelerate by demanding speed. You accelerate by reducing friction. That means resolving reuse drag, latency loops, and ownership drift. Not fixing people.

Let the System Learn and Lead

The most resilient organisations design for learning at every turn.

In complex environments, speed without reflection is chaos. But with the right system in place, speed and learning reinforce each other. Every feedback loop strengthens ownership. Every boundary clarifies autonomy. Every reuse pattern accelerates the next cycle.

The Fluid Organisation is not a mindset framework. It is a structural answer to agility, change, and continuity. Because in the end, the only culture worth scaling is the one our system makes possible.

No system learns faster than one designed to listen to itself.

Member discussion