Seniority, Impact, and the Wrong Questions

Why hiring for accumulation keeps organisations from scaling with leverage.

Most IT organisations say they want senior leaders. What they actually select for is accumulation.

More people. More scope. More time served.

Then they wonder why complexity keeps winning.

We keep asking the same questions when assessing seniority.

- How many people do you manage?

- How big was your scope?

- How long did you stay in each role?

These questions feel reassuring. They are easy to compare, easy to benchmark, and easy to justify. They give the impression of rigour. They also systematically miss the point.

They persist largely because the act of evaluation has been outsourced to systems and intermediaries that optimise for speed, comparability, and risk reduction rather than for understanding. Recruitment is often outsourced to people who are structurally incapable of assessing leverage, system design, or long-term impact, so they default to what is naively measurable, repeatable, and defensible.

Because none of them measure what actually matters at senior levels. They confuse visible control with actual leverage.

What We Keep Asking

Most hiring and promotion conversations still revolve around volume:

- Size of the organisation or area

- Number of direct and indirect reports

- Duration in role as a proxy for stability

- Breadth of responsibilities as a proxy for competence

This model assumes that seniority emerges naturally from accumulation. More people, more time, more scope.

That assumption is comfortable. It is also wrong.

What We Should Be Asking Instead

If seniority is about leverage, then the questions should change accordingly:

- What complexity did you remove?

- What decisions became unnecessary because of your work?

- What scaled without adding people?

- What continued to work when you stepped away?

These questions are harder to answer. They do not fit neatly into spreadsheets or scorecards. But asking them is not enough.

They require a shared understanding of leverage, system design, and long-term impact. And we do not currently operate in an ecosystem where these concepts are broadly understood, from recruiters to hiring managers to many IT organisations themselves.

Without that understanding, even the right questions are reduced to empty prompts, and the same superficial answers keep circulating. What should reveal seniority instead becomes just another performance exercise.

The Illusion of Outcome-Driven Leadership

Many organisations claim to be outcome-driven.

Yet their evaluation mechanisms optimise for control, visibility, and time served rather than for impact, resilience, or system health.

This is a classic measurement trap. When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure. Goodhart’s Law applies mercilessly here: numbers designed to observe outcomes are repurposed as goals, and the system predictably starts gaming them.

The deeper problem is not the metrics themselves, but the absence of a coherent storyline. Numbers without narrative are meaningless. Pretending to measure outcomes through isolated indicators does not create alignment or understanding.

A sound approach starts with a clear directional story, for example: customers genuinely love the product and recommend it without prompting. Only then does it make sense to introduce measurement, not as a goal, but as instrumentation.

At that point, two dimensions are sufficient: success and progress. Much like vectors in mathematics, you need both direction and magnitude. Direction comes from the narrative. Amplitude comes from measurement. Confusing the two leads to motion without meaning.

The result of getting this wrong is predictable. Leaders are selected for their ability to absorb complexity, not to eliminate it. Headcount grows. Dependencies multiply. Decision latency increases. The organisation becomes more fragile, not more capable.

What Real Seniority Looks Like

Real seniority often looks unimpressive on paper.

It shows up as:

- Fewer escalations

- Fewer coordination meetings

- Fewer critical dependencies

- Fewer people required to keep the system running

It is visible in calm operations, not in organisational charts.

Most tellingly, real seniority survives absence. When the leader steps away, the system does not collapse. It continues to function because decisions, interfaces, and responsibilities were designed to scale without constant intervention.

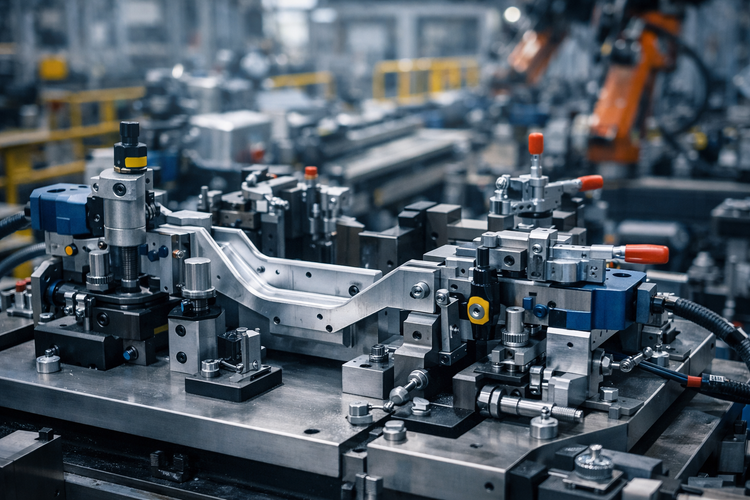

As an example, genuine Site Reliability Engineering organisations demonstrate this clearly. With the right system boundaries, automation, and operational discipline, a handful of highly senior engineers can support platforms used by hundreds of engineers. That is not understaffing. It is leverage, and it is one of the clearest signals of real seniority.

Yet these patterns are rarely recognised as seniority in hiring or promotion. They are often misunderstood, or even viewed with suspicion, because they do not fit the prevailing mental model of growth through accumulation.

The Cost of Asking the Wrong Questions

When we reward span instead of leverage, we promote presence over impact.

We end up with leaders whose value disappears the moment they leave the room, and organisations that cannot scale without continuously adding layers of management.

Then we act surprised when complexity overwhelms delivery.

A Different Definition

Seniority is not about how many people depend on you. It is about how many no longer have to.

Until our questions change, IT organisations will keep mistaking size for strength and growth for progress, and will continue to fail at growing, transforming, or thriving because they source and promote talent based on the wrong signals.

Member discussion