Monday Myth: The Unicorn Fallacy

A comforting myth

Every Monday, the same narrative resurfaces in IT: salvation will come from the next unicorn. A brilliant startup, a disruptive platform, a valuation detached from gravity. The belief feels comforting. It suggests that IT can fix itself from within, using the same ingredients that created the problem in the first place. The current AI boom provides a textbook example: massive capital inflows, inflated expectations, and a narrative of inevitability, long before any underlying economic reality has been proven.

This pattern defines the unicorn fallacy.

IT does not struggle because it lacks talent, frameworks, or ambition. It struggles because it has progressively disconnected from reality. Systems drifting too far from reality eventually collapse, regardless of how elegant they appear in slide presentations.

Recovery does not come from more unicorns. It comes from industry reclaiming IT.

Industry never had the luxury of illusion

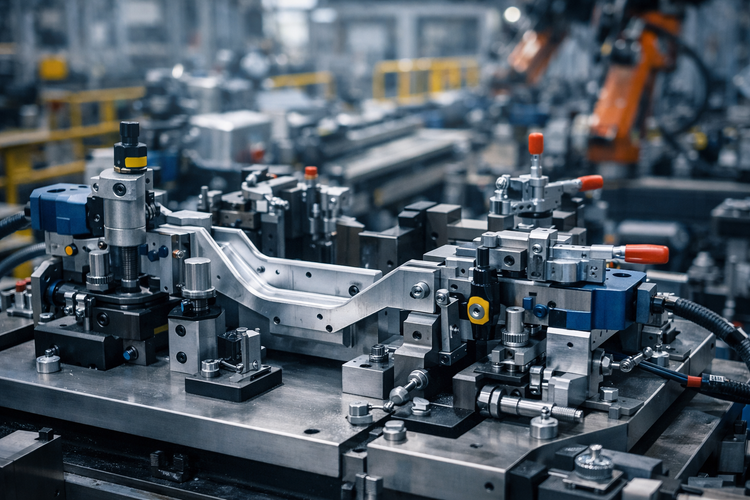

Real industries operate under constraints that much of IT has forgotten.

When organisations build aircrafts, defence systems, rail infrastructures, or metro access controls, failure does not manifest as a retrospective incident report. Failure appears immediately and visibly. People cannot pass barriers. Aircraft remain grounded. Systems offer no forgiveness. Failure can be lethal.

This context shapes a fundamentally different relationship with engineering:

- Craft outweighs velocity slogans

- Discipline supersedes narrative

- Seniority emerges through field exposure

- Accountability embeds structurally rather than symbolically

This stance does not stem from nostalgia. It stems from survival.

Aerospace, defence, transport, and heavy manufacturing carry decades, sometimes centuries, of accumulated know-how. That history represents operational memory rather than romance.

When such organisations internalise IT, they carry this mentality with them. Reality keeps the score, which makes sustained failure difficult to sustain.

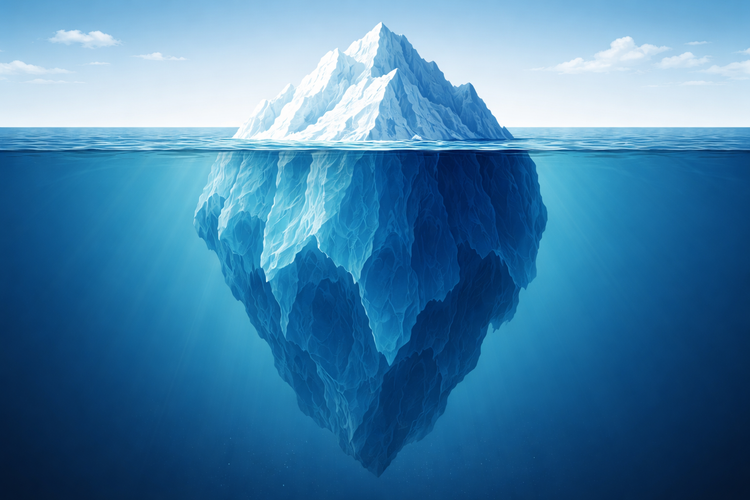

The Disconnection Index

To explain why unicorns collapse while industry endures, a simple mental model helps: the Disconnection Index.

The Disconnection Index measures the distance between an organisation’s technology and tangible everyday reality.

Index 0 : Fully coupled to reality

Embedded systems, physical infrastructure, and safety-critical platforms. Failure at this level triggers immediate real-world consequences. Examples include:

- Metro access systems serving hundreds of thousands of users daily

- Flight control and avionics

- Defence-grade identity and secure communications

Engineering discipline remains unavoidable at this level. Reality enforces correctness.

Index 1–2 : Indirectly coupled

B2B services selling to other technology organisations.

Value may still exist, but feedback weakens and consequences dilute. Additional abstraction layers absorb failure.

Index 3+ : Abstracted from reality

Pure platforms, marketplaces, or tooling layers lacking physical or societal anchors.

At this level, value depends entirely on confidence and capital. Once either erodes, collapse follows.

A striking sociological effect accompanies this state. The IT ecosystem actively promotes the idea that highly disconnected layers remain essential to modern life. Index 2+ systems appear framed as inevitable progress, even when their absence would barely affect everyday reality.

This illusion persists because most daily comfort does not originate from modern digital systems. Historians of infrastructure repeatedly show that roughly 70% to 80% percent of what enables functional daily life like clean water, sanitation, railways, electrical grids, building standards, and urban planning, emerged during the 19th century, shaped by steam, steel, and civil engineering, as described notably by Lewis Mumford and broader Industrial Revolution historiography.

This manufactured necessity sustains the illusion of progress. Movement replaces advancement, novelty replaces improvement, and activity masquerades as value creation. The unicorn economy feeds on this fabrication, presenting acceleration as progress while drifting further from reality.

Why unicorns look successful ... until the next bubble bursts

Highly disconnected environments generate predictable pathologies:

- Growth detached from real utility

- Platforms optimised for investors rather than users

- One or two anchor customers masking structural fragility

- Engineering organisations prioritising hiring speed over competence

- Accountability diluted across interfaces, contracts, and automated flows

In such ecosystems, responsibility rarely has a face. When an online bank blocks an account, a human point of contact often disappears behind chatbots and ticket queues. When a traveller becomes stranded because of a failed online booking, locating a person empowered to act proves difficult, if not impossible. Accountability dissolves both inside the unicorn and across the services it orchestrates.

When funding slows or a major client departs, reality surfaces abruptly. The same explanations recur: unexpected market conditions, strategic realignment, performance-driven reductions.

This pattern reflects neither chance nor misfortune. It reflects physics.

Systems detached from reality lose not only their ability to self-calibrate, but also their capacity to assign responsibility where it matters.

Craft versus theatre

Industry approaches engineering selection differently.

Credentials matter because they represent time spent mastering constraints. Training occurs under supervision. Juniors earn trust gradually. Seniors gain recognition through exposure to failure and responsibility.

Unicorn culture often reverses this logic:

- Titles precede competence

- Confidence substitutes experience

- Short bootcamps replace field apprenticeship

The outcome does not resemble innovation. It resembles theatre.

When reality intrudes through security incidents, scaling limits, or regulatory pressure, organisations lacking operational memory struggle to respond.

Industry lacks the luxury of avoidance. This constraint explains its durability. I explore this contrast in depth in Gears, Triggers and Systems and Foundations of Excellence, where industrial discipline provides a reference point for understanding IT drift and recovery.

When industry takes IT seriously

When industrial organisations choose to control data, infrastructure, platforms, and identity systems, they act deliberately.

They build.

They own.

They staff with engineers rather than titles.

This approach already defines standard practice across heavy industry:

- Shell operates substantial portions of its digital infrastructure, modelling platforms, and operational systems internally because energy production, safety, and regulatory compliance tolerate no fragile abstraction.

- Thales treats IT as a core engineering discipline integrated with defence, transport, and critical infrastructure systems, where failure carries immediate physical and political consequences.

- Airbus internalises large segments of its engineering IT stack, including simulation, manufacturing systems, and certification toolchains, because aircraft tolerate no software theatre.

This strategy does not pursue prestige through vertical integration. It pursues control, accountability, and long-term resilience.

Industry does not ask whether a system might scale in theory. Industry asks whether it will endure stress for decades.

The inevitable reset

The IT ecosystem will not reset through a better manifesto.

Reset will occur because:

- Capital tightens in a constrained world

- Customers reduce spending on highly disconnected services

- Real-world industries reassert ownership of critical systems

As resources tighten, individuals and organisations reconsider priorities. Survival restores clarity. Spending, time, and attention refocus on what shapes daily life directly. Convenience loses abstraction. Trust gains substance.

Spending then gravitates toward genuinely useful services delivered by industries trusted for decades. Scarce resources flow to providers demonstrating craft, continuity, and responsibility, rather than to entities whose value depends on narrative momentum.

This reset will feel brutal to those who benefited from abstraction without consequence. It will feel natural to those who never left reality.

Back to foundations

The unicorn fallacy persists because it flatters ambition while avoiding discipline. IT does not require more dreams. IT requires foundations.

Industry already knows how to construct them.

The future of IT will not follow the loudest platforms. It will emerge quietly through organisations that never forgot the purpose of engineering: solving real problems for real people under real constraints.

People more readily place trust in groups such as Thales to provide real‑world access granting in a Metro, or accept lightweight driving assistance from manufacturers such as Mercedes while retaining control themselves. In each case, technology supports life rather than replaces it, allowing people to remain grounded in the real world and to discard services built on fabricated necessity rather than genuine need.

After the reset, trust rather than innovation theatre will represent the scarcest and most valuable currency.

This insight does not introduce novelty. Years ago, trust, craft, and institutional legitimacy already formed the backbone of IT. That foundation did not disappear by accident. It eroded gradually, as speed, abstraction, and frictionless growth took precedence over responsibility. Somewhere along the way, progress became performative, and the substance that justified trust slipped out of reach.

The longer correction delays, the harsher its impact becomes. Systems avoiding correction accumulate fragility. When reality intervenes, it does not negotiate. It compensates.

Member discussion